How to use blended finance instruments to transform agrifood systems

16 February 2026 by Lysiane Lefebvre, Senior Policy Advisor, Private Sector & Sustainable Finance

Blended finance acknowledges a simple reality: private capital will not flow at the scale needed to transform the agriculture sector. It therefore deliberately combines public and philanthropic finance with private capital to share risks. This strategic use of finite public resources thus attracts private capital that would not otherwise be mobilised.

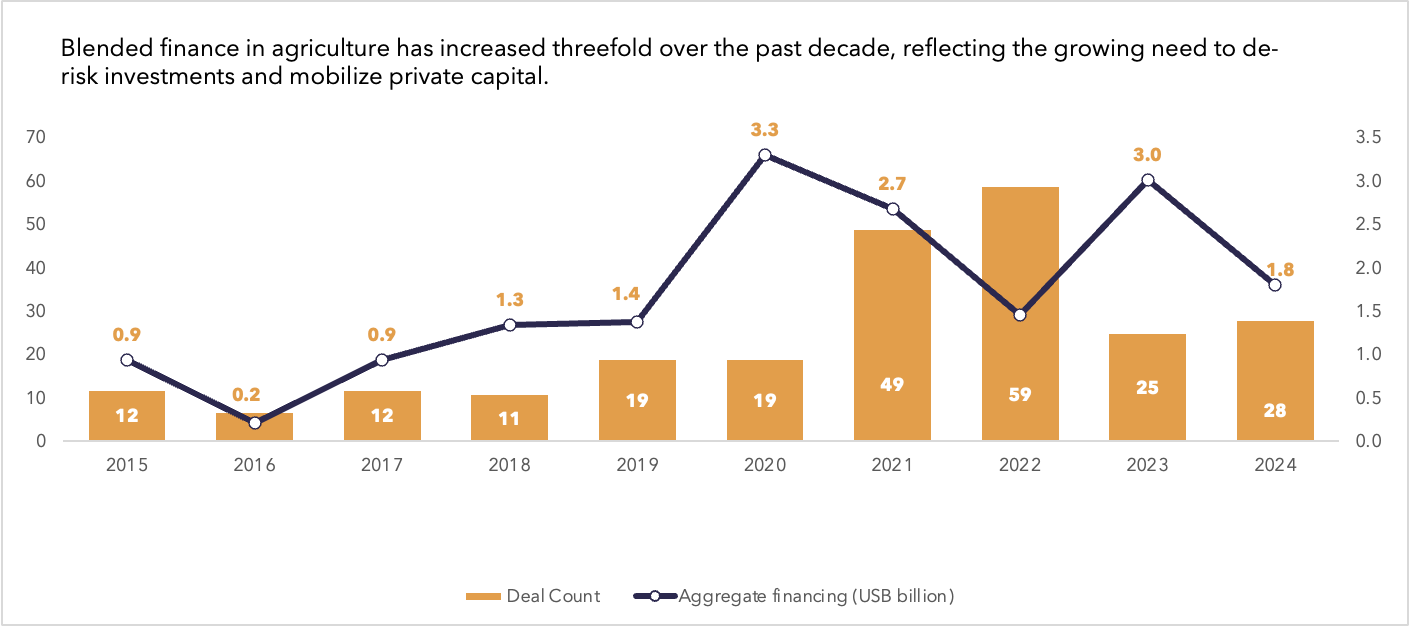

Blended finance is growing in importance. In agriculture, the number and volume of blended finance deals have expanded significantly over the past decade, with estimates suggesting a doubling of activity between 2015 and 2024 (see Figure 1). This growth points to a rising reliance on blended structures as a tool for de-risking investments, mobilising private capital, and scaling sustainable solutions.

Six ways to blend

Blended finance encompasses multiple tools for structuring risk and returns. The following section outlines six common approaches:

1. Risk-sharing instruments: reducing barriers to private investment

Risk-sharing instruments reduce downside risk for private investors by partially or fully transferring risks to public or philanthropic actors. First-loss capital, guarantees, and political or climate risk insurance provide financial protection if a project underperforms or faces external shocks. By cushioning potential losses, these tools make high-risk sectors like agriculture and land use more investable, particularly where climate impacts, price volatility, or political uncertainty would otherwise deter private capital.

The AGRI3 Fund is one example. It provides loan guarantees to partner banks, reducing credit risk and enabling them to extend financing to agrifood SMEs that would otherwise be deemed too risky. In Brazil, for example, AGRI3’s guarantee facility has enabled Rabobank to support investments that go beyond productivity gains to improve soil health, enhance carbon sequestration and strengthen long-term resilience. With AGRI3 backing, Rabobank Brazil offered a longer tenor and grace period on a loan to Van den Broek, a Brazilian soy, corn and cattle company to expand its regenerative farming practices.

2. Outcome-based finance: rewarding results, not activities

Results-based or outcome-based finance shifts the focus of development spending from activities and inputs to measurable outcomes. Under this approach, funding is made contingent on achieving pre-agreed results, such as improved soil health, increased climate resilience, or better livelihoods. This model reallocates performance risk away from donors and toward implementers and investors, while aligning incentives across all actors to prioritise effectiveness, innovation, and measurable impact rather than compliance with activity-based budgets.

An example is the Impact-Linked Fund for Eastern and Southern Africa, managed by Roots of Impact. The fund supports SMEs – including in the sustainable agriculture sector – by providing social impact incentives and impact-linked loans that lower financing costs when independently verified outcomes are achieved. Enterprises must demonstrate financial sustainability and raise commercial capital alongside outcome-linked payments, ensuring that growth, impact, and financial discipline are closely aligned.

3. Viability gap funding: making public value bankable

Viability gap funding offers targeted grants to projects that are economically justified but not yet financially viable on their own. By covering part of the upfront costs or bridging the revenue shortfall, these grants enable private investors to support projects that generate strong public benefits but lack sufficient commercial returns at market prices. This approach is especially useful for infrastructure and technology investments in agriculture, such as storage facilities, renewable energy systems, and cold chains.

India’s Viability Gap Fund demonstrates how this mechanism can mobilise private investment at scale. Administered by the Ministry of Finance, the fund provides grants of up to 20% of project costs, with a discretionary option for the government to offer an additional 20% for eligible economic or social infrastructure projects. By reducing upfront capital requirements, this approach encourages private participation in ventures that deliver essential public benefits. Launched in 2004, the scheme has proven successful and has been extended through 2025.

4. Concessional debt and patient equity: financing long-term change

Concessional debt and patient equity address the mismatch between the long-term investment needed for agrifood system transformation and the short loan tenors typically offered by commercial lenders. Instruments such as subordinated loans, low-interest “soft” loans, and patient equity accept lower or delayed returns in exchange for higher development impact. By taking a junior position or offering more flexible terms, these types of capital reduce risk for senior investors and give farmers and agrifood enterprises the time they need to generate sustainable cash flows.

One illustrative case is AgDevCo’s investment in Saise Farming Enterprises, a specialised potato seed company from Zambia. In 2016, AgDevCo provided USD 1.7 million in patient equity alongside USD 1.6 million in debt financing to support the greenfield development of the business, contributing to the development of an agricultural hub in Northern Zambia while creating sustainable jobs and benefiting smallholder farmers. In 2025, AgDevCo successfully exited its investment through an equity sale to a partner in the joint venture from the start, Buya Bamba Limited, demonstrating how patient capital can help build high-risk agribusinesses to maturity and attract follow-on commercial investors while strengthening the local food sector.

5. Technical assistance grants: building investable and impactful pipelines

Technical assistance grants support the non-financial components of investment that are essential for reducing risk and improving impact. Provided alongside capital, technical assistance can help projects assess financial feasibility, strengthen governance and management capacity, structure viable business models, and develop robust impact monitoring systems. In blended finance structures, technical assistance often plays a critical role in converting promising ideas into bankable investment opportunities.

For example, the Technical Assistance Facility of the Land Degradation Neutrality Fund provides tailored support to projects both before and after investment. It helps projects meet fund criteria (early-stage pipeline development), strengthen impact measurement and ESG compliance (advanced-stage pipeline development), and expand business model impact (post-investment support). This support has been instrumental in reducing investment risk and enhancing the social and environmental performance of funded projects.

6. Market-shaping mechanisms: building sustainable investment markets

Market-shaping mechanisms aim to alter the underlying investment landscape rather than de-risk individual transactions. Tools such as anchor investments, price incentives, and fund-of-funds structures seek to improve risk–return dynamics across entire sectors, reduce barriers to entry, and create conditions for private capital to flow more sustainably over time. These mechanisms are especially important where markets are fragmented, small-scale, or perceived as too risky for institutional investors.

The FASA Fund is one example of a market-shaping approach. Rather than investing directly in agrifood SMEs, the fund-of-funds invests in multiple agricultural investment funds as a junior equity provider. By supporting fund managers with both capital and technical assistance, FASA helps professionalise agricultural finance markets, diversify risk, and build a pipeline of investable opportunities across Africa’s agrifood sector.

Toward system transformation

Blended finance enables more than the mobilisation of additional capital. It supports longer-term investment horizons that are better aligned with the realities of agriculture and the climate transition, encourages innovation and impact in business models, and allows risks and returns to be better balanced across public and private actors. By doing so, it helps scale sustainable solutions that would otherwise remain too risky to attract commercial investment.

Most importantly, blended finance helps shift development finance away from isolated projects and toward broader systems transformation. Rather than focusing solely on individual transactions, it can be used to influence entire markets by changing risk–return dynamics, strengthening investment ecosystems, and creating conditions for sustainable finance to flow over time.

However, blended finance is not a universal solution. Leverage ratios, while useful for illustrating mobilisation effects, do not measure development impact or additionality. Impact can be defined too narrowly, and measurement remains complex and resource intensive. Moreover, not all interventions are suitable for private finance, particularly where public goods or highly uncertain benefits dominate. Blended finance also requires long-term commitment from both public and private actors, as market transformation and climate resilience cannot be achieved through short-term or fragmented financing approaches.

Outcome-based finance is one of the most promising approaches. Based on the idea that financing should reward real improvements, this approach creates stronger incentives for sustainable practices and makes externalities visible and valuable. By linking payments to independently verified outcomes, this approach helps ensure that every dollar invested delivers real, measurable benefits and strengthens the case for private capital to support long-term, climate-resilient transitions.

To read more about why the Shamba Centre is betting on outcome finance, click here.

Figure 1. Count and value of blended finance deals, 2015-2024. Source: Convergence, 2025